On the morning of December 28th last year, I woke up to news that struck me with the force of a bad portent: the Hardy Tree in St. Pancras churchyard had fallen. Only a little less than six months before, I had been in London and visited the tree for the first time. It was my second visit to London and, in fact, my second time visiting the old church and its quiet green space near the tracks and the canals—but the first time I was there, I didn’t know of the tree and wasn’t looking for it.

In the mid-1860s, Hardy worked as an architect for the firm of Arthur Blomfield, who was commissioned by the Bishop of London to level the St. Pancras churchyard in order to make way for an expansion of the Midlands Railway. In 1865, Hardy was the clerk of works for this project, supervising the exhumation of gravesites there. Apparently, it was he who piled the displaced tombstones into a kind of circular formation, at the center of which an ash tree grew. A plaque in the churchyard says that “the headstones around this Ash tree (Fraxinus excelsior) would have been placed here around this time,”[1] but stories from this December, in the Guardian and elsewhere, suggest that there is little evidence to support this claim.[2] Nevertheless, an ash tree grew: its roots pressed themselves between the massed grave-stones, heaving them up like a tumulus and pushing them apart like the petals of a flower, and its branches spread shade all over them.

Scholarly discussion of the Hardy Tree is scant. Indeed, even though Kester Rattenbury’s recent critical study, Thomas Hardy, Architect: The Wessex Project (2018), makes a connection between Hardy’s architectural work in London and the St. Pancras Hardy Tree, it does so by suggestion rather than citation. We know that Hardy grew up in a family of builders, began his formal education in architecture during his late teens, as an articled assistant to the Dorchester architect John Hicks, and moved to London to work for Blomfield in 1862. There, he made his entrance into a professional culture in which art, experiment, and philosophy were closely linked, and he reveled in it, attending the Great Exhibition, making rigorous museum visits and documenting them in his notebooks, and winning an essay prize from the Architectural Association. Rattenbury reconstructs an emerging intellectual arena in which Hardy’s ambitions, beyond the horizon of his day-to-day draughtsmanship for Blomfield, might have included the specific aspiration to become a literary architect.[3] Garbett, Ruskin, Pugin, and Morris would have been his models for writing at the intersection of architecture and criticism—thinking at the juncture of aesthetics and infrastructure that suggests the prototypical emergence of a mode we’d now recognize, perhaps, as theory.

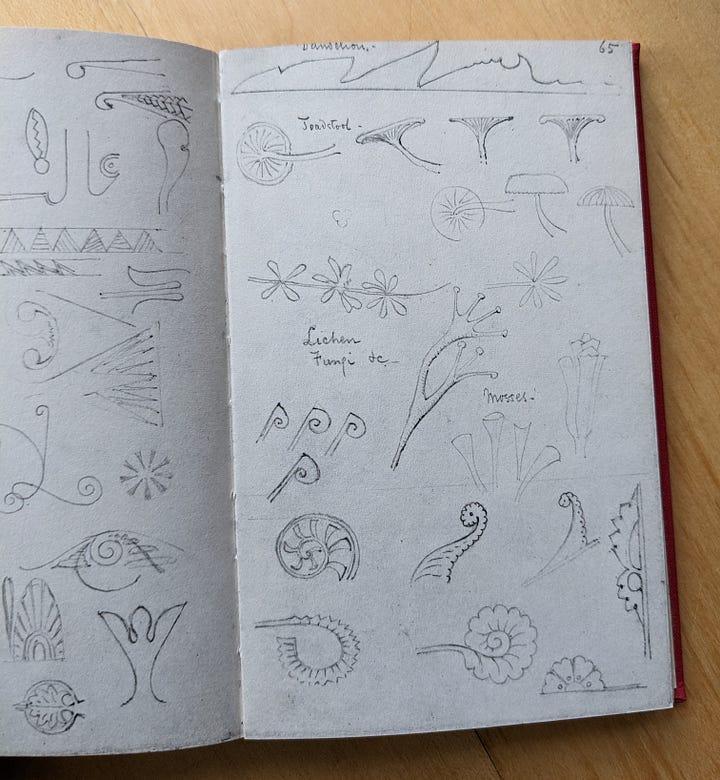

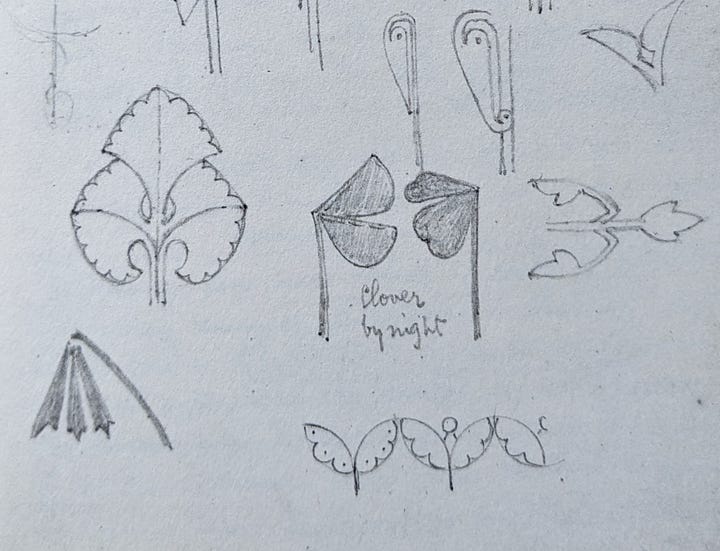

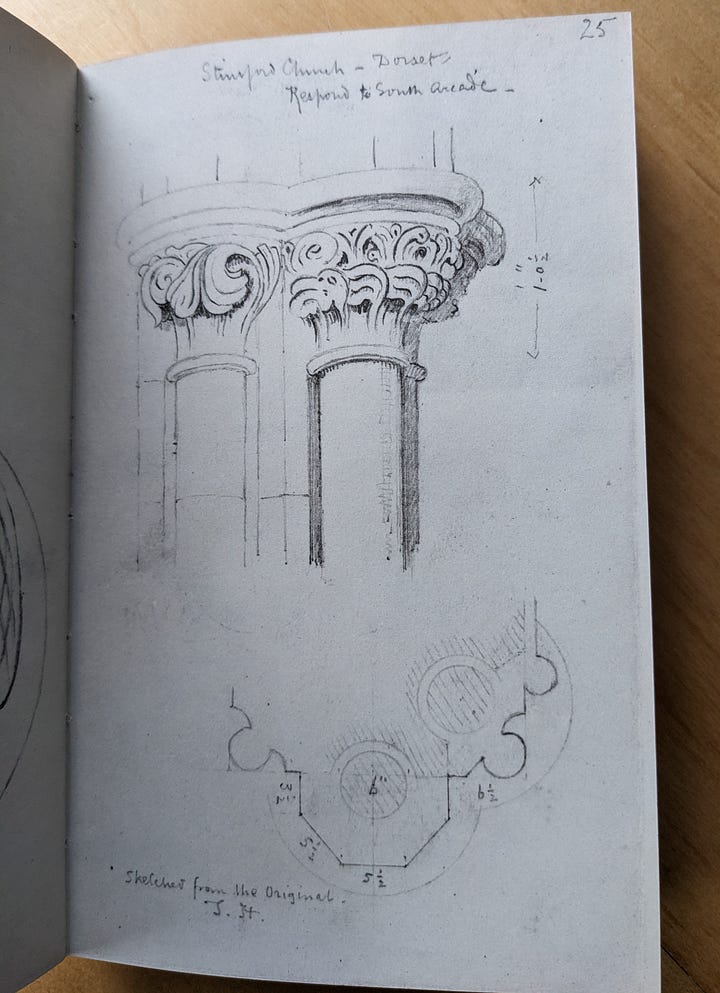

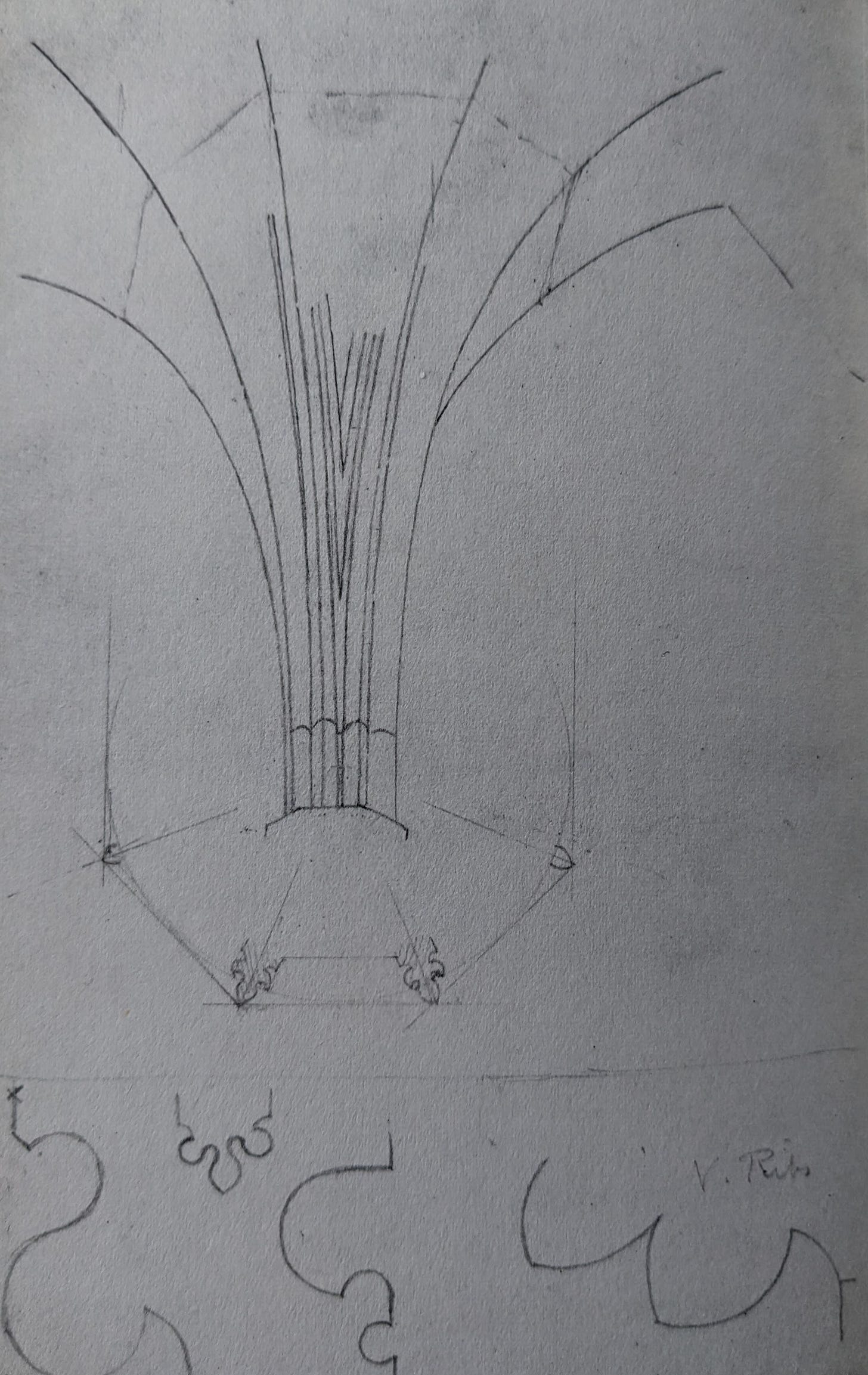

In the leaves of Hardy’s architectural notebook, collecting sketches from the 1860s through the 1890s, we can see traces of the experimental space in which he pursued an ongoing engagement with architectural thinking, even after he left Blomfield, returned to Dorset, and began trying to publish novels.[4]

The notebook contains an exquisite design language—sketches of bays, corbels, joists, and arch mouldings, floorplans—recording a wide vocabulary of Gothic ornament that references organic shapes like mosses, florets, and seedheads: dandelion, lichen, toadstool (fig. 1); a silhouette of clover leaves folded up for the night (fig. 2). You will find a sketch of “Church near the Downs. From the Hill,” dated 1866 (fig. 3), a detailed drawing of the arboreal cornices of columns in the Stinsford church (fig. 4), and a rendering of ribbed vaulting in St. Juliot Rectory, which looks like branches (fig. 5). But you will not find any plans, drawings, or sketches of the work undertaken in the St. Pancras churchyard, or any clear visual references to the monument known as the Hardy Tree.[5]

As a Gothic object, as an architectural structure, as monument, the Hardy Tree is endlessly suggestive. It fuses together the historic, the infrastructural, and the aesthetic in a site-specific way, memorializing the displacement of those whose resting places were disturbed to make way for the Midlands Railway. Hardy made only one explicit return to the upturned graves and displaced stones of St. Pancras, in a poem entitled, “The Levelled Churchyard” (1882). In the classic epitaphic gesture, the poem’s restless dead arrest the passerby:

O passenger, pray list and catch

Our sighs and piteous groans,

Half stifled in this jumbled patch

Of wrenched memorial stones!

The verse gives voice to nameless souls, but what they have to say is an echo of Hardy’s own resistance to practices of architectural restoration that seek to improve, to smooth away traces of time’s passing. The dead plead,

From restorations of Thy fane,

From smoothings of Thy sward,

From zealous Churchmen’s pick and plane,

Deliver us, O Lord! Amen![6]

To treat the Hardy Tree as a work of art—a work specifically attributed to Thomas Hardy—would entail, I think, stepping over the satin cord that separates scholarly research from lore; folk history and the stuff of urban legend. But whether or not the story connecting Hardy and the ash tree is true, this living monument is (was) a trace of the past that arrays before us a set of complex questions surrounding the realism of Hardy’s fictions and, broadly speaking, the scholarly concerns that constellate themselves around literary form. Who can speak on behalf of the voiceless? What happens when literary language gives voice to the absent and the dead? What can be more pressingly real, in narrative terms, than the resurgent presence of the past in the present?

The ash tree was already failing when I visited in July. It was a quiet afternoon. Outside the old stone church, I passed an elderly man and woman sitting on a bench and drinking white wine. A man was letting several half-grown, unleashed black dogs roughhouse at the far end of the churchyard, which put me vaguely on the alert. At the grave of Mary Wollstonecraft, visitors had left behind quartz pebbles, a lily, a broad yellow plane-tree leaf.[7] Otherwise, I was alone.

At a distance, I could see that the grassy area surrounding the tree was cordoned off with orange plastic mesh and at the foot of the tree, adjacent to the pile of tombstones arrayed around its roots, stood a pile of freshly sawed logs from a fallen limb. I approached circuitously, feeling tempted to step over the barrier. I couldn’t get as close as I wanted. Leaf-litter, sycamore balls, and wood-shavings littered the ground, giving the scene the air of a construction site.

The whole place was sere and yellowed, like most of London’s parks that summer, because of the drought. I had arrived at the tail-end of an intense heatwave, and although it was still very warm, it was neither as hot nor as humid as the subtropical mid-Atlantic city I’d traveled from. All around London, distressed trees gave green spaces an autumnal look: dry, crispy leaves trembled and silvered in unexpected gusts of cooler air. I seem to remember that it was very quiet within the gates of the churchyard. I can’t recall if I could hear the groan of buses pausing at the bus stop, or trains passing on the tracks below, or the barking of the dogs, or the conversation of the couple I’d passed, or the wordless, roaring omnipresence of the city.

Out the window of my childhood bedroom grew a pin-oak that cast sharp and tiny acorns onto the foot of our shared driveway. When I was lying in bed, its branches filled my whole view out that window. It rotted inside and had to be cut down one spring, before I returned from college for the summer. I remember that its absence was the first thing I saw when I opened my eyes that morning. But what startled me more than the empty space was the silence. That tree’s presence had supplied a wash of sound around our house: the sound of the wind rearranging its branches, the sound of leaves, of falling acorns, and sounds of all the life that it supported—nuthatches and woodpeckers, cicadas, mourning doves, gray squirrels, chipmunks, red-tailed hawks, tent-caterpillars, ants. So, maybe the silence (which is all I can recall from the churchyard) was simply the nearly-soundless susurration of the ash tree itself. Against the blankness of a bright and humid London sky, its branches spread in silhouette.

The ash tree’s trunk was cloven in a sturdy y-shape. Deeply ridged bark traced the frozen upward motion of the tree’s growth, spiraling out and around from its center. Its roots both anchored it down and pushed the trunk upwards, knuckling among the stones. Its limbs were pitted with healed scars. At the crown, you could clearly see where failing branches had been pruned away. Leaves grew from the living branches in trailing clusters.

As I perambulated on the path surrounding the tree, never able to make my way close-up, I was struck by its dynamism: the way its trunk yearned, firmly planted yet straining slightly leftwards; the way its canopy made abbreviated, arching gestures with the bare stumps of lopped limbs, green sprays and tresses, how the growth of the tree pulled the densely arrayed stones at its base out, around, and upwards.

Henri Lefebvre wrote, “Form either fails or improves; and this is how it manages to go on living.”[8] I observe: the roots and stones are densely interfused. Bark streams between the stones in a living way, like lava. It engulfs them; slowly pulls them out of the earth like teeth. It spreads some stones apart like fingers separating the pages in a book and presses others together. The trunk boils out of the top of the pile; it boils solidly upward like a column of steam, making whirls and boles. The bark folds and twists like flesh. It grows suckers, festoons of leaves that sprout abruptly from the old scars. In dying, it puts out shoot after shoot after shoot. The parts that aren’t living fall away and the live parts put out young, thin, and supple stems.

[1] The text of the plaque is cited in Bannerjee, Jacqueline, “A Thomas Hardy Gallery — Places Important in His Life and Writings,” The Victorian Web.< https://victorianweb.org/photos/hardy/74.html> Web. 20 Feb. 2023.

[2] “The Guardian View on the Death of the Hardy Tree” cites research by amateur historian and blogger David Bingham. The Guardian <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/dec/29/the-guardian-view-on-the-death-of-the-hardy-tree-a-legend-uprooted> Web. 28 Dec. 2022.

[3] Rattenbury, Kester. Thomas Hardy, Architect: The Wessex Project (Lund Humphries 2018), p. 25.

[4] Rattenbury, p. 29.

[5] For figs. 1-5 see Hardy, Thomas. The Architectural Notebook of Thomas Hardy, ed. C.J.P. Beatty (Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, 1966).

[6] Hardy, “The Levelled Churchyard” <https://www.hardysociety.org/media/bin/commentaries/1532428889.pdf> Web. 20 Feb. 2023

[7] It is not her final resting place. In 1851, the remains of Wollstonecraft and her husband, William Godwin, were re-interred in a family tomb at St. Peter’s Cemetery in Bournmouth by her daughter Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s son, Percy Florence Shelley (see Gordon, Romantic Outlaws. Random House: 2015).

[8] Lefebvre, The Critique of Everyday Life (Verso 2014)

I love the idea of Hardy as land artist / Hardy Tree as land art!

What you write about his formal cataloguing, his sketchbook, and his theoretical inclinations at the hinge of aesthetics and infrastructure actually remind me a heck of a lot of Thomas Browne, whom I'm writing about in my diss. In any case, thanks for sharing this!